Post war property: how we rebuilt Britain

Post war property: how we rebuilt Britain

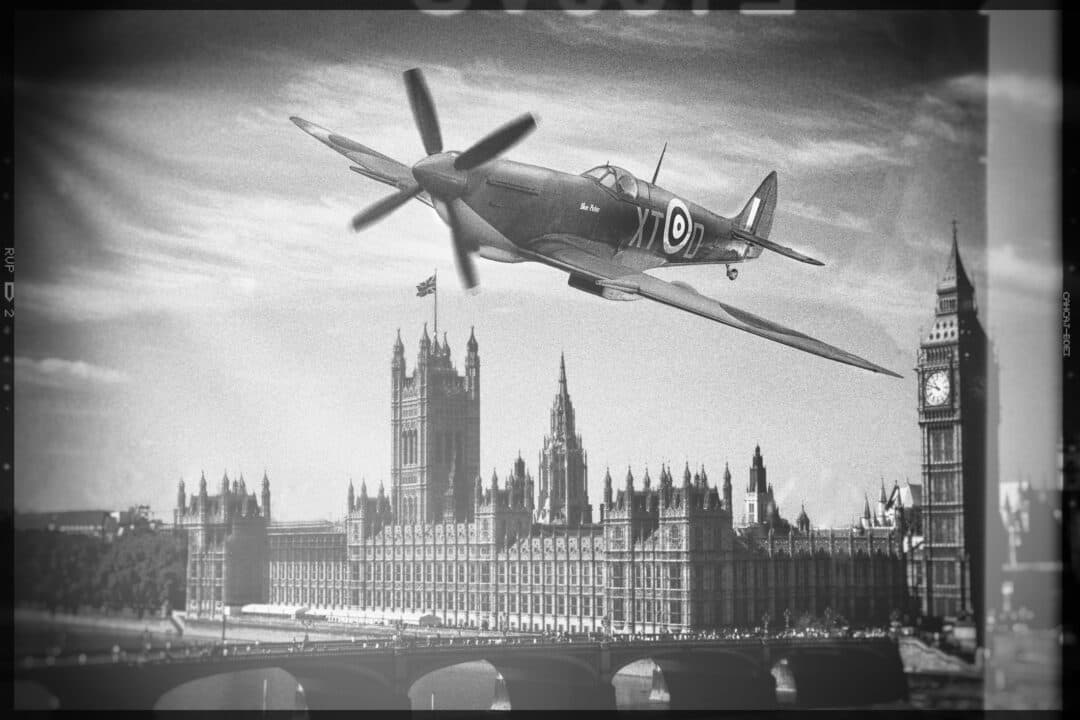

There’s nothing like a military milestone to focus the mind. The recent VE Day celebrations to mark 80 years since the end of World War II were a sobering reminder of how far we’ve come.

Some of the most moving stories came from evacuees. Almost 3.75 million people – mainly children living in urban areas – were sent away by their families, missing their homes as much as their parents. While many were welcomed into rural residences – cottages and farmhouses – some were housed in residential camps and large converted buildings.

Those that remained in at-risk cities split their time between the family home – often taped shut in case of a gas attack and in darkness so as not to alert bombers flying overhead – and air raid shelters.

Setting the scene: ambitious inter-war construction

Housebuilding had picked up pace following the end of World War I, with a reputed 290,000 new homes created in 1934 alone. To put this figure into perspective, approximately 217,911 new homes were built in 2024.

Some of the most popular property styles of the era were semi-detached and terraced homes, which fuelled the development of the ‘suburb’. Property design frequently followed Tudorbethan principles, with bay windows, steeply sloped gabled roofs and pebble dash exteriors.

In cities, new apartment blocks were springing up, reflecting the craze for Modernist and Art Deco design, although the mansion blocks, tenement buildings and rows of terraced homes erected in the late 19th century still housed thousands of urban dwellers.

For all its glossy brochures and indoor bathrooms, another property movement was gathering pace. The Slum Clearance Act was passed in 1930, giving power to Local Authorities to seize homes in the poorest conditions.

Stop-start slum clearances

The start of World War II stopped housebuilding and slum clearances in their tracks. An estimated 50,000 tons of high explosive bombs were dropped by the German Luftwaffe across 16 major cities. The toll on residential dwellings was monumental, with 60% of London’s buildings damaged or destroyed, and around 1.5 million people homeless.

After VE day in 1945, there was a pressing need to evaluate housing stock and slum clearances picked up pace. Unfit homes were demolished and replaced by social housing, with those who had been displaced rehoused as a priority.

Any port in a storm

Those that fell through the gaps were forced to make radical decisions. Historic documents show families living in caravans, shepherd’s huts, disused railway carriages, army bases and air raid shelters.

Perhaps one of the earliest documented planning disputes arose from one such desperate situation. A family living in an old trolley bus in East Sussex added a thatched roof. This started a debate within the local planning committee as to whether the bus could be classed as a permanent dwelling or cottage.

A lack of post-war homes also saw some families embrace what we think of as a modern property issue. Squatting was commonplace, with people moving into abandoned flats and hotels. The police and the military often intervened, preventing people from donating food and supplies. Eventually, the squatters would be evicted or arrested.

A new wave of new homes from 1946

Labour swept to power in 1946 and housebuilding was made a priority, with the era becoming a golden age for council housing. Under Clement Attlee, the Government built in excess of 1 million homes, 80% of which were owned by the council.

The the Government turned to new methods of construction to deliver this wave of dwellings. The prefab was born – a factory-built bungalow that took less than a week to build on site. The PRC home was also introduced. This structure, of precast, reinforced concrete, was also speedy to erect and less construction skill was needed.

The downside was their lifespan. Both prefabs and PRC homes were temporary solutions, therefore it didn’t totally solve the housebuilding crisis. The concrete deteriorated, the steel eroded, mould built up due to poor insulation and many contained asbestos. Some models still survive today but they are virtually unmortgage-able and have a greatly reduced market value.

Talk of the town

The New Towns Act was also introduced in 1946, becoming the most ambitious, large-scale town-building programme ever undertaken in the UK. It was designed to ease overcrowding in urban areas and replace bombed out accommodation. Dedicated organisations called Development Corporations oversaw the creation of 32 new towns across. The first was Stevenage, with residents coming from the London boroughs of Walthamstow, Edmonton, Leyton and Tottenham.

The promise was of more than just a home. London residents were enticed out of the capital to work on the construction sites, exchanging at least six months of graft for a guaranteed property. In fact, over a quarter of the first 2,000 houses completed at Stevenage went to building workers and their families.

Crawley, Hemel Hempstead, Harlow, Newton Aycliffe, East Kilbride, Peterlee, Welwyn Garden City, Hatfield, Glenrothes, Basildon, Bracknell, Cwmbran and Corby all followed Stevenage, as did the criticisms.

Being cut off from established networks of family and friend, monotonous architecture, the incubation of crime, corruption within councils and the erosion of traditional character were all levied but progress continued until the late 1970s. This is when ‘Right to Buy’ became Margaret Thatcher’s main election pledge and Development Corporations were phased out

The birth of modern private renting

It’s also worth noting the 1957 Rent Act. This was another Government reform introduced to improve the housing market. It was designed to encourage landlords to maintain, improve and increase the availability of private rental properties. A key aspect was revising how rent was set, introducing a formula based upon rateable value instead of rent caps.

The Act created the blueprint by which today’s private rental market still follows, although rent caps bring us right up to the modern day. Although not mentioned in the forthcoming Renters’ Rights Bill, rent controls are something the current Labour Government has alluded to in recent times.

Viewber – Viewings, Property Visits & more. The Big Bold Property Support Company.